Best Practices in Elementary Literacy Instruction Literature Review

Main Body

six. Approaches to Writing Instruction in Simple Classrooms

Vicki McQuitty

Abstract

This chapter focuses on the different approaches to writing didactics that teachers utilize in unproblematic classrooms. It includes an overview of each approach, a clarification of how each is implemented, an explanation of how each has been critiqued, and research prove about each approach'southward effectiveness. Information technology also provides recommendations about how elementary teachers can comprise the most promising components of each approach into their writing instruction.

Learning Objectives

After reading this affiliate, readers will exist able to

- draw different approaches to writing education;

- explain the benefits of each arroyo to teaching writing;

- hash out how educators and researchers have critiqued different ways of teaching writing;

- analyze the research conducted on dissimilar approaches to writing instruction;

- integrate ideas about effective writing instruction in elementary classrooms.

Introduction

Imagine you lot are a second grader at the beginning of the schoolhouse year. During writing fourth dimension your teacher tells yous to write almost your summertime vacation. What do you do? To an observer, it looks similar you saturday down at your desk, took out pencil and paper, wrote your story, and then drew a picture to accompany it. Yet, was the process really so simple? What happened inside your mind to get from the bare paper to a story well-nigh your summertime? What thought processes and skills did yous use to write this "simple" composition?

Writing is an important skill that is used throughout a person's life for bookish, professional, and personal purposes. If you are a proficient writer, much of the procedure is automatic and requires little conscious effort. Merely consider it from a child's indicate of view. For a novice writer, there are many things to remember about: forming letters on the page, writing left to right in a horizontal line, leaving spaces between words, using letters to represent the sounds in words, capitalizing proper nouns and the offset of sentences, and placing punctuation in appropriate places. At the aforementioned time, similar adult writers, children must also devote attention to generating and organizing ideas, including elements appropriate for the genre, choosing vocabulary to communicate the ideas conspicuously, and monitoring the quality of the text. Thus, writing places substantial cognitive demands on immature children considering they must attend to many things simultaneously in order to produce an effective text.

Because writing is such a challenging task, children need high quality instruction to develop their writing skills. Over the years, teachers have taught writing in many different ways, and components of each approach are yet institute in classrooms today. To empathise current writing instruction, it is helpful to understand how it has been taught in the past and why educators have introduced new means of teaching information technology over time. This chapter describes the different approaches that accept been used, shows how each has been critiqued, and includes inquiry evidence nigh the effectiveness of each arroyo. Each section besides includes recommendations for how teachers can best incorporate the components of each approach into their classroom practise.

Penmanship Approach

In the United states, the earliest approach to writing instruction with young children was teaching penmanship, a practice that dates back to the colonial era. Penmanship focused on transcription—the concrete act of writing—and it involved producing legible, accurate, and even beautifully formed letters on the folio. Children learned penmanship through faux and practise, and so they copied models over and over again from printed copybooks. Young children began by practicing single letters, followed by words, sentences, and eventually paragraphs. In some classrooms, the teacher led the entire grade to write letters in unison every bit she gave verbal commands: "Up, downward, left curve, quick" (Thornton, 1996). Sometimes children even expert the motions of writing, such as pushing and pulling the pencil on the paper, without writing actual letters. Regardless of how penmanship was taught, though, "writing" instruction consisted of copying rather than writing original words.

The goal of penmanship didactics was to ensure children formed letters correctly so they could produce neat, readable writing. However, students, and even many teachers, disliked the boring and mechanical drills. By the 1930s, some educators began to critique penmanship as an overly narrow approach to writing instruction (Hawkins & Razali, 2012). They suggested penmanship was not an end in itself, merely a tool for communication. This led some teachers to encourage children to write their own ideas for real purposes, such as making classroom signs or recording lunch orders. Teachers' manuals began to dissever penmanship and writing teaching, and penmanship was renamed "handwriting."

Handwriting pedagogy continued in well-nigh classrooms throughout the 20th century, merely it was given less priority equally the curriculum began to focus on writing original compositions. At the same time, some educators began to view handwriting as unimportant considering the apply of technology (e.thou., computers, tablets) has reduced the need for handwritten texts. Teachers devoted less and less time to formal handwriting drills, though many children even so practiced copying the alphabet in workbooks. Today, handwriting is usually taught in kindergarten through third grade, simply much less oft in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades (Cutler & Graham, 2008; Gilbert & Graham, 2010; Puranik, Otaiba, Sidler, & Greulich, 2014).

Even though handwriting has been taught in U.S. elementary schools for over two centuries, research on its effectiveness is relatively new. Recent studies show that handwriting is an important part of writing educational activity, only for different reasons than educators believed in the past. The appearance of the writing, which was the focus of the penmanship arroyo, is no longer considered important for its own sake. Instead, researchers now know that good writers possess fluent handwriting skills, but every bit strong readers possess fluent decoding skills1. They class messages quickly and automatically, without much conscious idea, which allows them to devote attending to the college level aspects of writing such every bit generating ideas and monitoring the quality of their text (Christensen, 2009). Consider a child who wants to write, "My domestic dog is chocolate-brown." Because her mind can remember only a limited amount of information at once, if she directs all of her attention to producing the letters K, y, d, o, and yard , she has no manner to concord the idea "is dark-brown" in her memory. Equally a event, she may forget what she intended to write at the finish of the sentence. Thus, the do good of handwriting instruction is to aid children grade letters effortlessly so they can recollect about their ideas rather than transcription.

Research shows that the most effective handwriting didactics occurs in short, frequent, and structured lessons (Christensen, 2009). Lessons should concluding x-20 minutes each day and focus on writing fluently and automatically rather than on forming perfect messages or positioning the letters precisely between the lines. It is helpful if teachers demonstrate how to form each letter so provide time for children to practice writing unmarried letters, private words, and longer texts. Programs exist for both manuscript and cursive writing, and they often teach the letters in a detail guild that has been institute to facilitate handwriting development. However, handwriting educational activity should only occur until children tin form messages fluently. As their handwriting becomes automatic, they should spend time writing for authentic audiences and purposes rather than practicing alphabetic character germination.

Rules-Based Arroyo

Teachers in the U.Due south. have taught children the rules of linguistic communication and writing since colonial times. Initially, these lessons occurred in the bailiwick of "grammer" and were considered split from "writing" (penmanship) didactics. Nevertheless, equally children began composing original sentences, grammer and writing pedagogy began to merge. Past the late 1800s, teachers viewed rules-based didactics as a way to meliorate students' writing (Weaver, 1996).

Rules-based instruction involves teaching children to correctly write words and sentences. It includes activities like identifying parts of speech communication, locating sentence elements such as subjects and predicates, learning and applying rules for subject-verb understanding and pronoun utilize, and practicing punctuation, capitalization, and spelling. 1 common exercise is judgement correction. Teachers provide sentences with linguistic communication errors and ask children to correct the mistakes. Students may also write original sentences for the purpose of practicing how to use language. For example, they may be asked to write a sentence that uses sure adjectives or homonyms accordingly. Other activities include adding prefixes or suffixes to lists of words, joining sentences by adding conjunctions, and irresolute fragments into consummate sentences.

Many educators take critiqued the rules-based approach to teaching writing as being decontextualized and inauthentic. It is decontextualized because children by and large write isolated words or sentences rather than total texts. It is inauthentic because, in the world outside of school, people do not write in decontextualized ways. They write stories, blogs, emails, and reports, and those compositions serve meaningful purposes—to entertain, inform, or persuade their readers. Writers communicate pregnant, not simply correct sentences, and so they must generate meaningful ideas and organize their thoughts logically. However, rules-based instruction does not address these higher level aspects of writing. Activities such every bit correcting sentences and adding prefixes to lists of words comport little resemblance to writing people use in their everyday lives.

Because rules-based instruction is decontextualized from writing authentic texts, it does not improve children's writing skills. As early as 1926, elementary teachers reported that, "the report of grammar did not seem to touch on pupils' voice communication and writing" (Cotner, 1926, p. 525). Afterwards enquiry provided empirical evidence to support what teachers noticed in their classrooms. Many studies synthesized by Myhill and Watson (2013) take shown that teaching children rules apart from meaningful writing tasks makes no affect on how they write. Even when students perform accurately on decontextualized activities, they often do non use that knowledge in their ain writing. For instance, a child who tin add punctuation to a sentence written by the teacher often incorrectly punctuates sentences in his or her original composition.

One activity similar to rules-based instruction but that research does support as effective is sentence combining (Myhill & Watson, 2013). In sentence combining, children merge ii or more than brusque, choppy sentences into i longer, more effective judgement. For case, they may be asked to combine Tim has a dog. The dog is tall and black into Tim has a tall, black dog. Practice combining isolated sentences seems to positively bear on students' original writing. Children who become proficient at combining sentences provided by the teacher tend to write longer, more circuitous sentences in their own compositions. Notwithstanding, it is important to recognize that most of the research on sentence combining has been conducted with loftier schoolhouse and university students. Some evidence exists (Saddler, Behforooz, & Asaro, 2008; Saddler & Graham, 2005) that it likewise positively impacts older elementary students' writing, but more research is needed to determine how constructive sentence combining is for younger students.

While decontextualized rules-based instruction does non better students' writing, there is some show that education grammar within the context of writing is beneficial (Jones, Myhill, & Bailey, 2013). A contextualized approach looks very different from traditional rules-based instruction. In a traditional approach, children might learn about adjectives by underlining them in sentences printed on a worksheet. In a contextualized approach, they add adjectives to their stories to depict the characters and the setting. The teacher might innovate adjectives equally "describing words" and ask the children to requite some examples. She then will show them how to use adjectives to create a vivid clarification of a story setting, and the students will use adjectives to create settings in their ain stories. Using adjectives in context, rather than on a worksheet, provides a meaningful purpose for learning about them. In addition, because children use their knowledge of adjectives directly to their writing, the quality of their writing improves.

Process Writing Approaches

Similar the name suggests, process writing educational activity focuses on the process of composing texts. In this approach, children larn to begin ideas, write rough drafts, and revise and edit those drafts. Process writing emerged in the 1970s, sparked by teachers' growing rejection of a rules-based approach. At the same time, professional authors, such as the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Donald Murray (Murray, 1968), began to advocate a "workshop" approach to writing teaching that engaged students in the same writing process that published authors used. Soon thereafter, researchers began to report writers every bit they composed original texts (Emig, 1971; Hayes & Flower, 1980). The findings of this research provided models of 1) what writers do equally they etch and 2) the composing process that occurs in writers' minds. Importantly, both this research and the instruction proposed by professional authors such as Murray were based on the writing processes used past adult writers rather than those used past children. However, despite this limitation, procedure writing became increasingly prevalent in elementary schools.

Because process writing began, in part, in response to criticisms of rules-based writing instruction, it emphasizes what rules-based approaches did not. Rather than education rules for creating sentences, it focuses on writing full texts and meaningful ideas, and it de-emphasizes spelling, punctuation, and grammar. Although educators and textbooks often talk about the process approach to writing educational activity, in reality it is many varied approaches that all share a focus on the writing process. Consider the writing instruction in the following second grade classrooms. Mr. Johnson assigns a writing topic to his class every Mon morning. 1 Monday he asked them to write about this prompt: "If you could be any animal for one day, what would you be? What would you do all day?" The students brainstormed ideas past creating a list of dissimilar animals and what each of those animals would do on a typical mean solar day. On Tuesday, each child chose an animal and wrote a draft of his or her story. On Wednesday, Mr. Johnson asked the children to revise by reading over their commencement drafts and instructing them to add 5 more than details. He showed them how to draw arrows to blank spaces on the paper to add words or sentences. On Thursday, Mr. Johnson returned the children'south stories for editing. Each child checked the spelling, capitalization, and punctuation in his or her typhoon and fabricated corrections. On Fri, the children copied their final drafts neatly onto clean newspaper and turned them in to Mr. Johnson. He graded the stories over the weekend and returned the papers on Monday.

In the classroom side by side door, Ms. Turner began writing time on Monday past telling the children they would be writing memoirs. Because the grade had read and discussed many memoirs in the previous two weeks, the children understood that they should write a personal story nearly an interesting or important feel in their lives. They brainstormed ideas by listing memories nearly fun things they had done, scary times they remembered, and moments they felt very happy or very sad. Once the children made their lists, Ms. Turner asked them to tell some of their stories to a partner. After xv minutes of storytelling, she said, "Some of yous told a story that your partner liked very much. If you think others would enjoy hearing your story, write it down so you can share it with the class." Some children began writing and others connected telling their stories to different friends in the class.

On Tuesday, Ms. Turner encouraged the children to cull another memory from their list and write about it. Some children wrote new stories, others read their drafts to a friend, and some began revising. While the children worked, Ms. Turner talked to individual students, reading their drafts and showing them how to make changes. She showed Marissa how to add describing words and showed Paul how to write dialogue. She also taught a brusque "mini-lesson" to the whole class about how to add together details that would help readers visualize the story's action. At the end of writing fourth dimension, two or three children volunteered to read their stories aloud to the class. The audience asked questions and offered suggestions for revising the stories.

Writing fourth dimension continued this way for ten days. Children wrote, revised, and shared their work, and they received feedback from friends and from Ms. Turner. Some children wrote and revised several stories, while some wrote only i or two. Each day Ms. Turner taught a mini-lesson virtually how to write a good memoir and met with children for writing conferences. After 2 weeks, she invited students to choose one story that they wanted to publish. Using speech-to-text software, the children entered their stories into a word processing document and began to edit. Ms. Turner taught them to use spellcheck, and they edited their own and others' work. During writing conferences, she taught some to capitalize the beginning of sentences and showed others how to use quotation marks. Afterwards editing was complete, Ms. Turner printed the stories and bound them together into a class book. Each child read his or her published story to the class, and the school librarian put the book in the library and then other students could read it.

Down the hall, in Ms. Harrison'southward classroom, writing time on Monday began with the instructor announcing, "It'southward time to write." The children enthusiastically scattered around the room, grabbing pencils and notebooks. For the next 25 minutes, they wrote in their journals and talked to one another. Ms. Harrison allowed them to cull their ain topics and write any type of text, simply most children wrote stories almost characters from their favorite movies and television programs. Some wrote an unabridged story, others wrote a judgement or ii, and a few drew pictures without writing any words. Ms. Harrison sat at her desk while the children worked and read annihilation that a child brought to her. "Bully job!" she said to each one. Once a month, she collected the children's journals and put a smiley face at the top of each page.

Although each of these teachers used a "process writing" approach, many differences existed in their instruction. In Mr. Johnson's room, the teacher assigned the writing topic, and everyone moved through the writing process together: brainstorming on Monday, drafting on Tuesday, revising on Wednesday, and editing on Thursday. Students wrote alone and only the instructor read their piece of work. In Ms. Turner's class, children chose their own topics, moved through the process at their own step, got feedback from peers and the instructor, and shared their writing with classmates. They also received both private and group instruction from the teacher. In Ms. Harrison'southward class, the students chose their own topics and moved through the writing procedure at their own pace, but they received no directly instruction from the instructor.

People sometimes wonder why these different ways of pedagogy are all called "process writing instruction." This happens because teachers, and sometimes researchers, tend to characterization whatsoever approach in which children typhoon, revise, and/or edit every bit "process writing." Research shows that teachers who use process writing teaching implement it in different means (Troia, Lin, Cohen, & Monroe, 2011). As a result, the term "process writing" means many different things.

Evaluating the benefits of process writing instruction is challenging for two reasons. First, few high quality experimental studies2 have directly examined this arroyo (Pritchard & Honeycutt, 2006). As a outcome, causal evidence nigh its effectiveness is limited. Second, because teachers implement process writing differently, it is hard to guess this approach holistically. Consider the three classrooms described above. If a researcher set out to study process writing, which of the classes would he or she include? The education in i classroom might be much more effective than the educational activity in the others, notwithstanding each is considered to be "process writing." Perhaps a more of import question than "Is process writing effective?" is the question, "What specific activities within process writing educational activity lead to the best learning outcomes for children? Yet, much more research is needed to answer this question (McQuitty, 2014).

Despite some of the difficulties of studying process writing, some general conclusions virtually the effectiveness of this approach tin exist drawn from selected studies that have been done. A meta-analysisiii of 29 individual studies indicates that process writing is moderately effective at teaching children to write, though it is less constructive with students who have writing disabilities than with students who are average or high achieving writers (Graham & Sandmel, 2011). The meta-analysis included only studies that occurred in classrooms with like types of procedure writing educational activity. The education in each classroom had these features: 1) extended opportunities for writing; 2) writing for existent audiences and purposes; three) emphasis on the cyclical nature of writing, including planning, translating, and revising; 4) student ownership of written compositions; 5) interactions around writing between peers as well as teacher and students; 6) a supportive writing environment; and 7) students' self-reflection and evaluation of their writing and the writing process. So, we can conclude that process writing instruction with these 7 features is moderately constructive for average and high achieving writers but merely minimally effective for struggling writers. All the same, if teachers implement process writing instruction with other features, those approaches might exist more or less effective for these groups of children.

While more research is needed about the specific features that make procedure writing pedagogy effective, some educators accept critiqued the approach. For example, Lisa Delpit (2006) has argued that in some classrooms (like Mr. Johnson's and Ms. Harrison'due south), the focus on procedure means in that location is no didactics about the writing product. This creates difficulties for students who practise not already know the characteristics of good writing. For instance, stories usually progress in chronological lodge, while advisory reports are organized effectually topics and subtopics. Children who have read many stories and informational books will know these organizational structures, but those with few reading opportunities may not. Because some students may not take access to as many books as their classmates, they may lack cognition of how stories and reports are organized. If their teacher simply teaches the writing procedure and ignores instruction about how the text should exist organized, certain children volition be at a disadvantage.

Process writing approaches are relatively popular in elementary classrooms and probably offer some benefits. Writing, past its very nature, is a process, so education children how to appoint in that procedure makes sense; however, teachers must carefully consider the specific practices they include in their process writing instruction. Enquiry evidence does support several detail practices that teachers should implement as part of a process arroyo (Pritchard & Honeycutt, 2007). Get-go, they must show students specific ways to meliorate their writing. For example, they can demonstrate how to add details to a story and provide fourth dimension for children to add details to their own stories. This explicit teaching about how to create a quality text helps students more than than simply telling them to draft, revise, and edit. Information technology also answers Delpit's (2006) concern that some children will not know the features of expert writing or how to produce it.

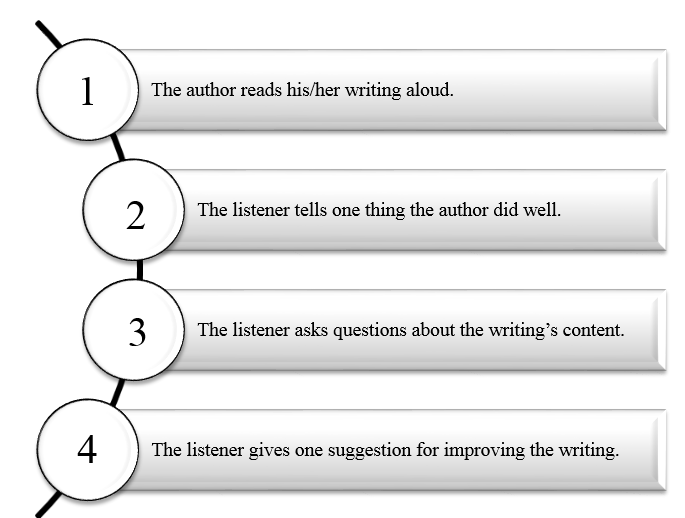

2nd, children tin can benefit from interacting with peers during the writing process. They tin can learn from one some other and help each other improve their writing. All the same, students do not automatically know how to assist their peers, so teachers must show them how to give meaningful feedback. I effective practice is to give children criteria for responding to peers' writing (Pritchard & Honeycutt, 2007). Some teachers requite students a protocol that outlines how to engage in peer response (run across Figure 1). When children receive specific instruction nearly how to give feedback, they are better able to help ane another.

Finally, there is some evidence that children should engage in the writing process flexibly rather than rigidly (run into McQuitty, 2014 for a review). Some children may need more time to write their start drafts, while others may demand more time for revision. Writing conferences, in which teachers read over children's drafts with them and provide feedback, also allow for flexibility. The teacher can provide individualized instruction in writing conferences, such as showing one child how to organize a paragraph logically and showing some other how write topic sentences. Maintaining a flexible approach to process writing allows teachers to meet each child's specific instructional needs.

Genre Approaches

Although process writing provided a much needed response to ineffective, decontextualized language activities, the focus on process sometimes meant teachers ignored the quality of the writing itself (Baines, Baines, Stanley, & Kunkel, 1999). In some classrooms, children drafted, revised, edited, and shared their work, just their writing never improved. Particularly troubling was the fact that some children—usually white, centre course English speakers—seemed to excel in process writing classrooms while others—commonly those from historically marginalized groups—did non. This fact led genre theorists to critique process writing and offering genre approaches every bit an alternative.

Genre approaches to writing instruction focus on how to write dissimilar types of texts. The notion of genre is grounded in the idea that writing is situational, and so what counts as "good" writing depends on the context, purpose, and audience. For example, texting a friend and composing an essay are two very unlike writing situations. A "good" text message communicates ideas informally and efficiently, and background information is non needed because the author and reader share common knowledge and experiences. A text which states, "Ok meet you at 10" suffices. A skillful essay, however, has very different characteristics than a text message. An essay author must utilize a formal tone, fully explain all ideas, provide examples, and use complete sentences. Thus, the form of the writing is tied to the state of affairs in which it occurs.

Teachers who use genre approaches teach almost different writing situations and the forms required in each ane. Instruction usually begins with children reading and analyzing a genre (Dean, 2008). In a unit nearly informational texts, the teacher volition read many advisory books aloud to the class and ask the children to read informational books on their own or in small groups. Subsequently reading, they discuss questions such as, "What's the purpose of informational texts? When practice authors write them? When do readers read them? What do readers await when reading this genre? What are the features common to informational writing?" In one case children understand the purposes and features of the genre of informational books, they would so begin to write their own.

Genre approaches answer critiques of procedure writing past emphasizing the text and explicitly instruction the features of different text types. Nonetheless, considering teachers oftentimes integrate genre instruction with procedure writing or strategy approaches (described beneath), it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of genre instruction by itself. Enquiry does testify that children need repeated exposure to a variety of genres (Donovan & Smolkin, 2006), so it seems plausible that genre instruction would benefit students. Notwithstanding, we currently have no confirmation that genre instruction lone improves children's writing.

Genre approaches may become more common in uncomplicated schools because the Common Core State Standards for English language Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Scientific discipline, and Technical Subjects (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Principal State School Officers [NGA& CCSSO], 2010) for grades kindergarten through v are organized around 3 types of texts children should learn: narrative, advisory, and persuasive. Therefore, the CCSS support a genre approach to teaching writing. As genre educational activity becomes more than popular, though, there is concern that teachers will focus also much on the forms and features of the different genres rather than how genres are situational (Dean, 2008). For example, a teacher might only teach that persuasive texts must country an opinion, requite reasons for the stance, and group the ideas logically (NGA & CCSSO, 2010). While it is important children know these features, it is as of import that they empathize why people write persuasive texts, how the text features help authors create an constructive argument, and how authors might need to vary the form of their argument to persuade different audiences. Thus, while genre approaches hold potential equally effective means to teach writing, it is currently unclear the all-time way to implement them. More research is needed to provide farther evidence about how teachers should use genre instruction in their classrooms.

Strategy Approaches

Strategy approaches to writing instruction teach children the planning, drafting, and revision strategies used past skilled writers. These strategies are specific steps that guide students through each function of the writing process. For instance, children might larn the planning strategy Pw (Harris, Graham, & Mason, 2006): Pick my ideas (make up one's mind what to write about), Organize my notes (organize ideas into a writing program), and Westwardrite and say more (continue to modify the plan while writing). The teacher would teach this strategy through a serial of steps: 1) develop the background knowledge students need to employ the strategy; ii) discuss the strategy and how it volition ameliorate students' writing; iii) demonstrate the thinking processes used while implementing the strategy; 4) provide support as students utilise the strategy, such as working together with a partner; and 5) take students utilize the strategy independently.

Strategy instruction typically incorporates elements of both process writing and genre teaching. Later on learning the Pow strategy, children learn other, genre-specific strategies for planning and drafting. When learning virtually persuasive writing, they acquire TREE: Tell what yous believe (state topic judgement), provide 3 or more Reasons (Why do I believe this?), End it (wrap it up correct), and Examine (Do I take all the parts?). This strategy teaches the features of persuasive writing and guides students through planning, drafting, and evaluating their texts. Subsequently completing their drafts, they might larn the SCAN revision strategy (Harris & Graham, 1996): Scan each sentence. Does it make Southense? Is it Connected to your belief? Tin can yous Add more?Note errors. Using POW, TREE, and SCAN together guides students through the process of writing a persuasive piece and directs them to include features of the persuasive genre.

Strategy educational activity is a structured, systematic, explicit approach to teach writing. Teachers thoroughly explain the steps of the writing process and directly demonstrate both the thinking and the actions required to implement each footstep. Children do each strategy, get-go with teacher and peer support and so on their own, until they accept mastered it. Thus, while strategy education teaches the writing process and genre features, it is more systematic, explicit, and mastery-oriented than either process writing or other genre approaches. These features likewise seem to go far more constructive. Numerous experimental studies have shown strategy instruction to exist more effective than other types of writing educational activity (Graham, 2006). However, strategy didactics is hands broken downwardly into steps, which means that information technology is easier to inquiry than other approaches. This may be 1 reason why more than experimental studies most strategy education have accumulated compared to enquiry on other means of instruction writing.

Despite the strong evidence that strategy instruction helps children learn to write well, information technology is not widely used in elementary classrooms. This reality may be because teachers view information technology as formulaic or considering it is more teacher-centered (rather than student-centered) than other approaches. Of grade, teachers who use strategy instruction implement it in different ways. For instance, some teachers use IMSCI (Read, Landon-Hays, & Martin-Rivas, 2014), a somewhat less directed method of didactics strategies. This approach begins with Inquiry in which the teacher and children read various examples of a genre together and create a chart of the genre's characteristics. This inquiry is more consistent with other genre approaches than with models of strategy educational activity in which the instructor directly describes and explains the genre features. However, the side by side step of IMSCI, Thouodel, involves explicit education. The teacher directly demonstrates the thinking and actions required to plan, draft, and revise. The final steps—Shared writing, Collaborative writing, and Independent writing—are also similar to other strategy approaches in which students first piece of work closely with peers and the teacher before writing independently. All the same, IMSCI is less mastery-oriented and somewhat less instructor-directed than other strategy instruction approaches.

Because the level of explicitness and teacher management tin can vary depending on how strategy didactics is implemented, the question for teachers is, Just how straight and explicit must strategy instruction be in order to be effective? Researchers currently have no clear answer to this question. Studies do indicate that more than explicit pedagogy particularly benefits struggling writers (Graham, 2006), only some educators think that teacher-directed approaches pb to shallower learning than approaches in which students take a more agile role. Perhaps the best communication for teachers is to integrate strategy educational activity with less explicit process writing methods (Danoff, Harris, & Graham, 1993). Such integration might offering the benefits of both explicit didactics and student-centered approaches to learning.

Multimodal Writing Approaches

Multimodal approaches to writing instruction acknowledge that people in the 21st century write differently than in the past. In addition to composing traditional, linear, paper-based texts, we also—perhaps more often—compose digitally. Writing digitally is not just a affair of typing on the calculator rather than writing on newspaper. Digital texts apply many different modes to communicate, and authors can develop proficiency in composing each one. Consider a typical webpage. In addition to written words, information technology may also contain photographs, artwork, audio, video, and text boxes that allow readers to mail their own ideas. Designing and coordinating these various elements requires different skills than writing a words-only story.

Digital writing also links texts differently than traditional writing. Many traditional stories are linear; the author expects readers to proceed from the starting time to the end rather than jump frontwards and backward through the pages. In contrast, retrieve well-nigh how people read digital texts. A typical sequence might be: Read half of the home page, click on a video link, lookout half the video, click dorsum to the dwelling page, click on a hyperlink, read the starting time two sentences of the new folio, then click on another hyperlink to yet another page. The options for reading a website are endless compared to the options for reading a bound book. Every bit a result, authors of digital texts that include hyperlinks create a set of pages that can be read in almost any gild.

The word "blueprint" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009) is oftentimes used to draw digital composing because many elements must be considered beyond the written words. Unlike traditional books, there are many options for page size and orientation, font style and size, layout of elements on the page, apply of white space, and modes of communication (music, video, pictures, written words). The author of a digital text employs writing, graphic design, and possibly fifty-fifty musical, movie making, and visual art skills to design the text. Furthermore, considering digital texts tin can be interactive, authors must also consider if and how they will provide opportunities for readers to brand comments, participate in polls or surveys, or otherwise add to the text.

Although digital, multimodal writing is prevalent in our everyday lives, many elementary students keep to etch traditional pencil-and-newspaper texts in school. This may occur considering the engineering science needed to write digital texts is too expensive or because the curriculum focuses on traditional paper-based writing. Still, some teachers are providing opportunities for children to combine traditional and digital writing. For case, Ms. Bogard'due south third graders composed digital stories (Bogard & McMackin, 2012). They created graphic organizers on paper that depicted the story events and used the organizers to tell their stories aloud and sound record them. Then, with a partner, they listened to the recordings and received feedback and suggestions. Based on the feedback, each child created a storyboard on paper past cartoon the pictures that would appear in the story and the narration that would accompany each image. They likewise planned how to create the images: have photographs, depict and scan to the computer, create video clips, or create still images using software. Finally, they put all of the elements together—images and sound recorded narration—and used software to create their digital stories.

While digital texts are the most probable types of multimodal writing, some teachers accept encouraged children to create multimodal texts that are paper-based. For case, while writing memoir stories, children in a 4th grade class (Bomer, Zoch, David, & Ok, 2010) created books that contained pop-ups, glued-in photographs, and objects such every bit ribbons and stickers. Some students made their books interactive past concealing some of the content with sticky notes and instructing readers to "lift hither." Others fastened notecards to the book and so readers could write back. All the children incorporated 3-dimensional elements such every bit handmade cardboard boxes filled with confetti, fold out maps, or a packet of sequentially numbered cards that told part of the story. Thus, multimodal writing does not crave digital tools.

Because schools have simply recently begun to include digital and multimodal writing in their curricula, merely a few studies have examined this approach. Qualitative research, such as that conducted in the classrooms described above, shows that uncomplicated children are capable of producing multimodal texts. Withal, considering multimodal writing requires writers to create and coordinate different media, teachers may need to provide a high level of support to ensure children's success. For case, Ms. Bogard (described in a higher place) engaged her students in 2 cycles of planning and revision for their digital stories. First, they created a graphic organizer of the story events, told the story orally and listened to their recording of it, and received feedback from peers. This allowed them to compose and revise the content, which ensured that the story fabricated sense, independent of import details, and followed a logical sequence. They then created storyboards that allowed them to plan every image and write the words that would back-trail each image. Each footstep of the process was needed to ensure the children could coordinate the multiple visual and audio elements of their digital stories. Simply request children to write multimodally, without providing a process to support their writing, would likely be unsuccessful.

Summary

Many dissimilar approaches to writing didactics have been used in elementary classrooms. Some approaches, such equally short, structured handwriting lessons and strategy instruction, have a strong inquiry base of operations to back up them. Other approaches, similar penmanship and rules-based instruction are ineffective in improving children's writing skills. Many approaches, including teaching grammar in context, process writing, teaching genre, and multimodal writing, are promising practices that need more enquiry to decide the best ways to implement them. Teachers usually do, and probably should, combine the all-time elements of each approach in guild to provide the most constructive instruction for their students. They must too seek out newly published inquiry on writing instruction then they can continue to make informed decisions most the best ways to teach.

Questions and Activities

- What are the different approaches to writing instruction? Depict each approach and explicate what the research says about its effectiveness.

- Based on the research show, how would yous pattern effective writing teaching for elementary children? Describe the elements you would include and explain why you would include them.

- Describe the approaches to writing educational activity you experienced as a student. How helpful did you observe each approach in supporting and developing your writing skills? Given what you now know nigh writing instruction, what would suggest that your teachers do differently? Explain your proposed changes and why yous suggested them.

- Notice writing pedagogy in an elementary classroom or view 1 of the videos of writing instruction bachelor online. Clarify the approaches the instructor incorporates into his or her instruction. How did the children respond to the dissimilar parts of the instruction? Explicate how effective the pedagogy seemed and why you lot evaluated that mode.

Spider web Resource

- Components of Constructive Writing Instruction: http://www.ldonline.org/spearswerling/Components_of_Effective_Writing_Instruction

- Every Child a Reader and Author: http://www.insidewritingworkshop.org

- National Writing Project: http://world wide web.nwp.org

- Project WRITE: http://kc.vanderbilt.edu/projectwrite/

- Videos about writing teaching: https://www.learner.org/resource/series205.html

References

Baines, L., Baines, C., Stanley, G. K., & Kunkel, A. (1999). Losing production in the procedure. English Journal, 88, 67-72. doi:10.2307/821780

Bogard, J. Chiliad., & McMackin, M. C. (2012). Combining traditional and new literacies in a 21st-century writing workshop. The Reading Teacher, 65, 313-323. doi:ten.1002/TRTR.01048

Bomer, R., Zoch, Yard. P., David, A. D., & Ok, H. (2010). New literacies in the material earth.Language Arts, 88, 9-20.

Christensen, C. A. (2009). The critical role handwriting plays in the ability to produce high-quality written text. In R. Bristles, D. Myhill, J. Riley & M. Nystrand (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of writing development (pp. 284-299). 1000 Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, Thou. (2009). "Multiliteracies": New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, four, 164-195. doi:10.1080/15544800903076044

Cotner, Due east. (1926). The condition of technical grammer in the elementary school. The Elementary School Periodical, 26, 524-530. doi:10.1086/455935

Cutler, L., & Graham, Southward. (2008). Principal course writing educational activity: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 907-919. doi:ten.1037/a0012656

Danoff, B., Harris, Chiliad. R., & Graham, South. (1993). Incorporating strategy pedagogy inside the writing process in the regular classroom: Effects on the writing of students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Reading Behavior, 25, 295-322. doi:ten.1080/10862969009547819

Dean, D. (2008). Genre theory: Educational activity, writing, and beingness. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Delpit, L. (2006). Other people'south children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York, NY: The New Press.

Donovan, C. A., & Smolkin, L. B. (2006). Children's understanding of genre and writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing inquiry (pp. 131-143). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Emig, J. (1971). The composing process of 12th graders. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Gilbert, J., & Graham, Due south. (2010). Teaching writing to unproblematic students in grades 4-6: A national survey. The Uncomplicated School Journal, 110, 494-518. doi:x.1086/651193

Graham, S. (2006). Strategy instruction and the pedagogy of writing: A meta-analysis. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 187-207). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Graham, S., & Sandmel, K. (2011). The process writing approach: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Research, 104, 396-407. doi:ten.1080/00220671.2010.488703

Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (1996). Making the writing process piece of work: Strategies for composition and self-regulation. Brookline, MA: Brookline Books.

Harris, Chiliad. R., Graham, S., & Mason, L. H. (2006). Improving the writing, noesis, and motivation of struggling young writers: Furnishings of self-regulated strategy development with and without peer back up. American Educational Inquiry Periodical, 43, 295-340. doi:ten.3102/00028312043002295

Hawkins, L. Thousand., & Razali, A. B. (2012). A tale of iii P's–Penmanship, product, and process: 100 years of unproblematic writing instruction. Language Arts, 89, 305-317.

Hayes, J. R., & Bloom, Fifty. S. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In Fifty. W. Gregg & Eastward. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cerebral processes in writing (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Jones, S., Myhill, D., & Bailey, T. (2013). Grammer for writing? An investigation of the furnishings of contextualised grammar education on students' writing. Reading and Writing, 26, 1241-1263. doi:10.1007/s11145-012-9416-1

McQuitty, V. (2014). Process-oriented writing instruction in elementary classrooms: Evidence of effective practices from the research literature. Writing and Education, 6, 467-495. doi:ten.1558/wap.v6i3.467

Murray, D. One thousand. (1968). A author teaches writing: A applied method of education composition. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Myhill, D., & Watson, A. (2013). The office of grammar in the writing curriculum: A review of the literature. Child Language Educational activity and Theory, thirty, 41-62. doi:10.1177/0265659013514070

National Governors Association Heart for Best Practices & Quango of Chief Country Schoolhouse Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Scientific discipline, and Technical Subjects . Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://world wide web.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/

Pritchard, R. J., & Honeycutt, R. L. (2006). The process approach to writing instruction: Examining its effectiveness. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 275-290). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Pritchard, R. J., & Honeycutt, R. L. (2007). Best practices in implementing a procedure approach to pedagogy writing. In S. Graham, C. A. MacArthur, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), All-time practices in writing teaching (pp. 28-49). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Puranik, C. S., Al Otaiba, South. A., Sidler, J. F., & Greulich, L. (2014). Exploring the amount and type of writing teaching during language arts instruction in kindergarten classrooms. Reading and Writing, 27, 213-236. doi:x.1007/s11145-013-9441-8

Read, S., Landon-Hays, K., & Martin-Rivas, A. (2014). Gradually releasing responsibleness to students writing persuasive texts. The Reading Instructor, 67, 469-477. doi:10.1002/trtr.1239

Saddler, B., Behforooz, B., & Asaro, K. (2008). The effects of sentence-combining teaching on the writing of fourth-form students with writing difficulties. The Journal of Special Education, 42(2), 79-90. doi:ten.1177/0022466907310371

Saddler, B., & Graham, S. (2005). Effects of peer-assisted sentence-combining instruction on the writing performance of more and less skilled young writers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 43-54. doi:ten.1037/0022-0663.97.1.43

Thornton, T. P. (1996). Handwriting in America: A cultural history. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Troia, G., Lin, S. C., Cohen, Due south., & Monroe, B. W. (2011). A year in the writing workshop: Linking writing educational activity practices and teachers' epistemologies and behavior nearly writing didactics. The Elementary School Periodical, 112, 155-182. doi:x.1086/660688

Weaver, C. (1996). Educational activity grammer in context. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Endnotes

1: For more detailed information near the part of fluency in expert reading, see Chapter 3 by Murray in this textbook.

ii: For information about using research to determine the effectiveness of an instructional approach, come across Chapter ii by Munger in this textbook.

3: For more data about meta-analysis, run into Affiliate 2 past Munger in this textbook.

Source: https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/steps-to-success/chapter/6-approaches-to-writing-instruction-in-elementary-classrooms/

0 Response to "Best Practices in Elementary Literacy Instruction Literature Review"

Post a Comment